12th June 2019

EC Women in Digital Scoreboard 2019: Use of internet higher yoy in Czechia

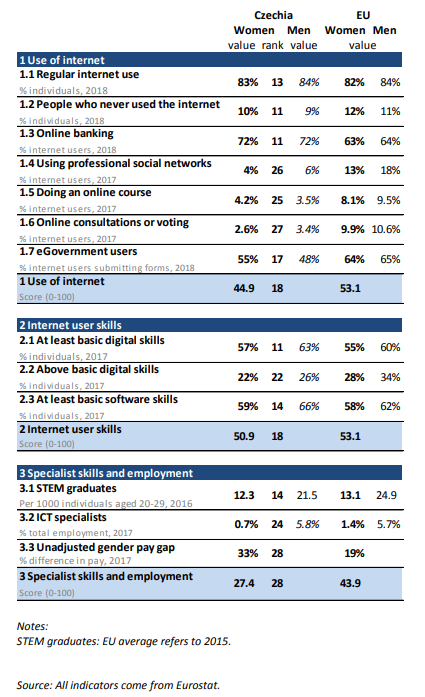

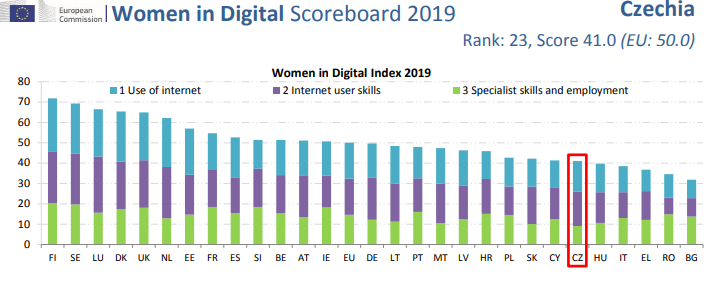

The Commission’s Women in Digital (WID) Scoreboard monitors women’s participation in the digital economy. The scoreboard assesses Member States' performance in the areas of Internet use, Internet user skills as well as specialist skills and employment based on 13 indicators. As of 2019, the Women in Digital (WiD) scoreboard is an integral part of the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI).

Some of the key findings of the WiD 2019 scoreboard show that:

- Just like last year, Finland, Sweden, Luxembourg, and Denmark have the highest score on the WiD Scoreboard.

- Women are the least digital in Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, and Italy marking no change from last year.

- There is a strong correlation between the WiD Index and the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Member States who lead in digital competitiveness are also leaders in women in digital.

- Luxembourg, France, and Spain are more advanced in women in digital than in overall digital.

- There is a gender gap in all the 13 indicators at EU level. The gap is largest in ICT specialist skills and employment.

- Only 17% of ICT specialists are women. The same ratio for STEM graduates is 34%.

- Women in the information and communication sector earn 19% less than men.

- In digital skills, there is a gender gap of 11%. The gap is higher for above basic skills and especially for those above 55 years

>> All country reports.

Czechia ranks 23rd out of 28 EU member states, compared with 24th place in 2018. The country recorded improvement in the "Use of Internet" category >> the "Use of eGovernment" parameter, among others. In 2018, 32% of women and 35% of men were eGovernment users, while in 2019 the share reached 55% and 48%, respectively, according to the Commission's data.

Gender pay gap, i.e. % difference in pay remained at 33% in 2018.

>> View full country profile for Czechia.

Source: European Commission, Women in Digital Scoreboard 2019

>> Read also some reated take-aways from OECD Skills Strategy 2019 on Czechia:

- Several countries experience uneven skills development performance over the life course. For instance, in the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic and Sweden, adults’ skills are strong compared to youth’s skills, and conversely, in Ireland, Korea, Poland and Slovenia, the skills of adults are weak compared to those of youth. Differences in performance among age groups at a given point in time can be explained by a variety of factors. These include a change in educational attainment and the quality of compulsory education over time, as exemplified by diverging trends in PISA in recent years, e.g. the Czech Republic, Slovak Republic and Sweden show a negative trend, while Ireland, Poland and Slovenia show a positive trend. Other factors include changes in tertiary education attainment and in the quality of tertiary education, the effect of skills atrophy over time, and changes in the accessibility and quality of adult education and training. While the combination of these factors make a direct comparison of performance in different stages difficult, the uneven skills development performance over the life course highlights the need for broad policy action at all stages of the life course.

- In Austria, the Czech Republic and Germany, for instance, foundational skills of the population are above average, but the effect of the parents’ education level on skills is comparatively large.

- On-the-job training can be one way to reach many adults, yet employer-sponsored training remains limited, concentrated in large firms, and most commonly available to highly skilled employees. Significant differences exist between countries, with Greece, Hungary and Poland continuing to lag behind with fewer than one out of two enterprises providing training in 2015. In Latvia, Norway, Sweden and the Czech Republic, this rate exceeds 90%.

- Almost all the top-performing countries with respect to employment and labour force participation tend to have small differences in performance between men and women and different education levels even when adjusted for relevant characteristics. Good examples are the Scandinavian countries, New Zealand and Switzerland. Still, strong overall labour market performance is not a guarantee for an inclusive labour market. In Japan, for example, employment and labour market participation are high, but there are still comparatively large differences between the employment of men and women. In the Czech Republic and Slovenia, employment levels are above OECD averages, but the low educated are lagging behind.